Do you remember the last time you read a book that you simply couldn’t put down? When you can’t stop reading a good novel, it is likely because the flow of the writing carried you through from sentence to sentence and from page to page. In this blog post, I’ll show you how you can turn your paper into that page-turner story for your reviewers and readers.

Unfortunately, when reading papers, readers often get lost – unlike that good book you devoured recently. The contents of papers are usually a little harder to digest than those of novels, but that’s not the only reason why readers get stuck: Many scientific authors underestimate the power of flow in writing. And because what you are communicating in your paper is complicated, you have even more reason to help your readers (including your reviewers) to move from sentence to sentence without needing to stop and think.

In other words, if you want your papers and to be read (and cited), you need to do most of the work for your reader. And one important part of this is implementing flow in your writing.

How do we achieve flow in writing?

To achieve flow in your text, it should be clear why exactly you are providing certain information at exactly the point you do. The key to this is having a great structure in your article. For example, if you cover three different topics in one paragraph and don’t clarify how they relate, the paragraph will lack coherence and be hard to read.

Another crucial part to achieving flow is to always provide enough information so that your reader can comprehend each sentence or each part of a sentence in your text based on the information provided thus far: The information you provide in your paper should build on each other.

You can achieve this by starting each sentence by referring to information that was provided in the or a previous sentence before introducing new information.

A Simple example of flow in writing

Let me give you a silly example to clarify what I mean:

In this example, “walk” in the second sentence is old information that was provided in the first sentence, and “forest” is the new information. In the beginning of the third sentence, “forest” gets reiterated before providing new information.

By the way, the scenario described in these sentences is totally realistic 😉

In the above example, old and new information were introduced in order, which makes it easy for the reader. Let’s have a look at this example, where the old information isn’t provided before introducing new information:

The flow in these sentence is worse than in the first example. It’s still easy to read these sentences because the content isn’t hard.

A real example of flow in writing

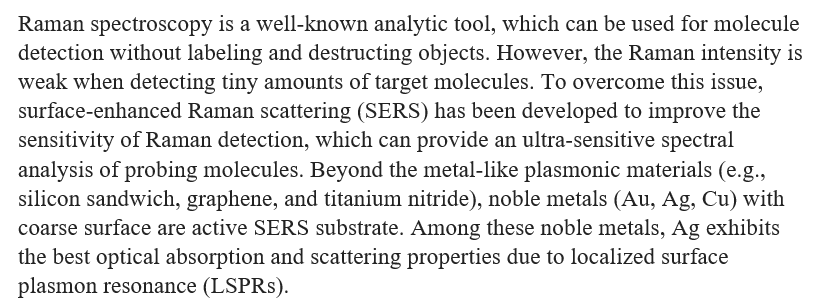

But how about some actual scientific writing that may require your brain to do a little bit more work than reading about Zuza’s life? To give you an example, I lifted a paragraph from the Introduction section of a random paper*. I won’t mention the authors’ names here – not because I don’t want to give them credit but because I do not want to shame them. The problem of missing flow is really common, and I picked this example randomly.

Below is the (almost) original paragraph that I only lightly copy-edited, e.g. by removing the reference numbers. I did not change the sentence structure.

This paragraph is not too bad! It contains all the information the reader needs, and it moves from the more general to the more specific. Below, I highlighted the different pieces of information that are being introduced and then referred to.

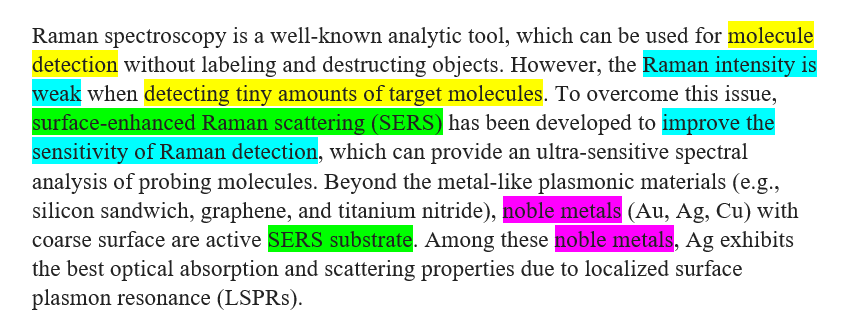

You may already have guessed that I would suggest to improve the flow in this paragraph by rearranging the information provided, i.e. by moving information highlighted in the same colour closer together. When you read the restructured paragraph below, notice whether you found it easier to understand than the above version:

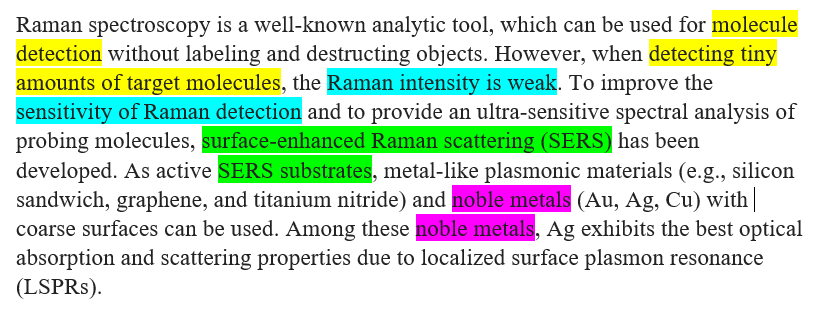

And here’s the same version of the paragraph showing all the changes I’ve made:

Isn’t it amazing how such small structural changes can hugely improve the flow and thus readability of scientific writing?!

Has this tutorial been useful to you? Let me know by posting a comment below!

*Reference: Scientific Reports 9, 17634 (2019). The article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Does writing for a high-impact journal feel intimidating? Partly because you’ve never received proper academic writing training?

In this free online training, Dr Anna Clemens introduces you to her template to write papers in a systematic fashion — demystifying the process of writing for journals with wide audiences.